GEORGE FICKLIN

GEORGE FICKLIN

FREE CREOLE OF MOBILE

For the past several years, I have been researching my 16 second great-grandparents in various counties of Alabama. This research has led me to tackle many uncomfortable realities as an African American. The Cleveland Historical Society was my jumping off point. A small membership fee and many hours sitting in front of microfiche machines were small prices to pay. Reading census hieroglyphics was exciting and frustrating, but brought me closer to the names and places I sought. Enthusiasm ruled over frustration, and eventually I got the hang of it.

Then I discovered the internet and away we go! Ancestry.com yielded a community of relatives with the possibility of closing a few gaps and revealing new avenues of investigation. Alas! It was not to be. It seemed that no one had yet ventured as far as I, and it was time to step up my amateur status. So, here we are, at the proverbial 1870’s brick wall. Do we climb over it? Ignore it? Or just ram our way through? I opted for taking it apart, brick by brick. Then, reading a source citation on ancestry, I found FamilySearch. It has proved to be the most productive besides the ADAH – the Alabama Department of Archives and History.

Since, George Ficklin was my first brick, his life and place are the focus of this writing. There wasn’t much to go on. Initially, I had to discern whether he was or was not George Augustus. The Ficklings of Baldwin County, Alabama, seemed a well-documented family. After all, they were in every census since 1790.

Others may encounter the very same genealogical traps as separating one individual or one family from another. I hope this writing proves encouraging, in that, if an amateur can achieve some measure of success, it’s possible for anyone.

It seemed obvious, at first, that George Ficklin and Thomas Ficklin were somehow related. But how? George Ficklin was a distinct individual that made his mark on his place and time. He purchased real estate, possibly for his aging mother to live out her waning years. He was a church-going man that contributed to the founding of a landmark church. He fathered eight daughters and sought to ensure their marital status. He chose a difficult yet prosperous trade in order to provide for his family.

The question arose whether George Ficklin was aided by some congenital benefit in his endeavors. Was he just a hard-working man of color? Or, was he endowed with the caste supreme, i.e. color status, in an area of the world that rewarded one for his color (or lack thereof)? Did he have help? For a man of color, living under the yoke of possible enslavement, deportation if identified as a Native American, and a host of codified indignities too numerous to highlight, he did well.

Was George Ficklin free? How likely was a slave to buy property in 1860 Alabama? Why couldn’t I find a marriage record for him? Was he the “Geo. Ficklin” in the 1855 Alabama Census?

Where does one find the answers to these questions besides Ancestry.com?

Perusal of the below footnotes will give some idea of the available resources used to answer the foregoing questions. It is my sincere wish that they are helpful.

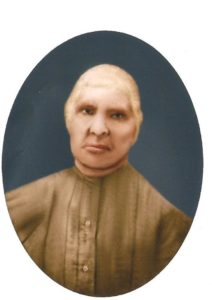

George Ficklin was my maternal 2nd great grandfather. He was born in Mobile, Mobile County, Alabama in 1834, according to his Civil War Draft Registration papers of 1863. He was not a slave prior to Emancipation was the hypothesis, based on the following items of evidence:

1) He purchased property in 1860. (The property was definitely bought by my ancestor rather than George Augustus Fickling.) The deed lists a “George Fickling,” and not “George Augustus Fickling.” It was in Township 2. Geo. A. Fickling’s widow resided in Township 4, Baldwin County, Alabama, in 1870.

George Augustus Fickling was another George Fickling that resided in Baldwin County Alabama. It was necessary to research both in order to eliminate one.

2) The George in question was NOT George Augustus Fickling, born 1827, in Baldwin County, son of Thomas Fickling, Sr. and Caroline. George Augustus married Laura Mirvin, and died during the Civil War in 1861. That George always used his middle name, “Augustus,” (except for the 1855 Alabama Census where no middle initial was recorded for either George). That was an initial point of differentiation between the two brothers. It is very likely that they knew each other since they lived in the same county with so few inhabitants, and were so close in age.

3) George Ficklin enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1864, on the Union side, at Warrington, Florida, to serve at Dauphine Island, for the duration. Hostilities ceased after the Battle of Mobile Bay in 1865. (There is some question as whether he was drafted or enlisted voluntarily.) This detail is not dispositive of his having been free prior to the Emancipation Proclamation of January, 1863.

4) George Ficklin married Mahala Morris, and not Laura Mirvin.

5) George Ficklin was enumerated in the 1870 United States Federal Census, in Baldwin County, Alabama, with his wife, Mahala and their children. (George Augustus was deceased.)

6) George Ficklin, of Montrose, Alabama, purchased land from Fanny P. Foster, in Baldwin County, Alabama, in 1870. The property abutted Thomas and Francis Cypert’s land. Both Fanny Foster, and her second husband, Richard Foster were free “mulattos,” i.e. creole, enumerated in the 1850 United States Federal Census for Baldwin County, Alabama.

7) Laura Mirvin, widow, remarried Robert Slaughter, and started life anew.6

8) George Ficklin was enumerated in the 1880 United States Federal Census, in Baldwin County, Alabama, with his wife, Mahala and their children.

9) George Ficklin was instrumental in founding the Macedonia Missionary Baptist Church, in Daphne, Baldwin County, Alabama, during Reconstruction. Whether he contributed land or money has not been clarified, as of this writing.

10) George Ficklin registered to vote in 1867. He was one of three Ficklin(g)s to register. One may deduce that he was related by blood to two other male Ficklings in Baldwin, at that time, namely, Thomas, Jr. and Charles.

11) George Ficklin was a farm laborer in 1870, but became a teamster by 1880. Teamsters made more money.

12) George Ficklin died 05 October, 1889, in Montrose, Baldwin County, Alabama. He was survived by his wife, Mahala, and their children. He was laid to rest at Montrose Cemetery, Montrose, Baldwin County, Alabama.

13) George Ficklin and Mahala Morris Ficklin’s children, as enumerated in the 1870 and 1880 U.S. Federal Census were the following persons:

1. Percy Walker Morris, 1854 – 1935 – stepson m. Susannah Alexander ; mother of Virginia Morris Lemont;

2. Caroline Ficklin, 1861 – 1932, m. Edward aka Edmund Bailey, (my great-grandmother, mother of Caroline Elizabeth Bailey Stradford)

3. Millie Ficklin, 1863 – 1904, m. Frank Reed ; father of Gertrude Reid; last married Charles Vivians;

4. Elizabeth Ficklin, 1866 –[before 1900], m. George Smith

5. Amelia Ficklin, 1869 – 1919, m. Augustus Jones

6. Mary Ficklin, 1871 – 1898, m. Samuel E. Taylor

7. Georgia Ficklin, 1874 – 1906, died unmarried.

8. Helena Ficklin, 1875 – 1964, m. Walter Joyce

9. Lucretia Ficklin, 1877 – 1952, m. Henry Pickett

14) The land purchased in 1860, was in Township 2 aka Bay Minette, but George didn’t live there. The only nonwhite Ficklins residing in Township 2, in 1870, were Charlotte Ficklin, age 70, Jane Ficklin, age 10, and Virginia Ficklin Harrison, age 30. They must have been George’s relatives, and plausibly his mother, niece and sister, respectively. These Ficklins were also persons of color or creole.

15) The largest free nonwhite population lived in the two counties of Mobile and Baldwin, Alabama, before the Civil War, and enjoyed freedom unlike the remaining counties of Alabama.

16) The only “Charlotte,” born in Mobile, Alabama, in 1800, as recorded, was Charlotte Ryan. In Creole Mobile, #230 is the number corresponding “with an extensive card catalogue system in the Cleveland Prichard Memorial Library.” There were many Carlotas, but only one “Charlotte.” There were no Ficklin(g)s. The names “Charlotte” and “Caroline” have the same etymology. It was customary to name the eldest daughter after her grandmother.

17) Thomas Fickling, Sr., born 1797, in South Carolina, died before 1860, in Baldwin County, Alabama, was the only Fickling of record, who would intersect with Charlotte Ficklin, born 1800, in Alabama, died before 1900, in Baldwin County, Alabama, in both age and vicinity, as a possible father for George. Charlotte (Ryan) was married to a Mr. Fickling, or lived in concubinage.

18) Charlotte’s children were namely, Louisa Ann Ficklin Ellis, (Rev. Jeffrey Ellis was George’s brother-in-law, and officiated at his daughters’ weddings.) George Ficklin, Virginia Ficklin Harrison, Jane Ficklin (more likely granddaughter due to Charlotte’s advanced age), and possibly more. Whoever fathered her children, was obviously in a long-lasting and committed relationship. She adopted his name, which occurs in a marital situation. “One emerging pattern of free Negro society is that of sexual continency and family stability.”

19) If Charlotte was a free woman of color, her children were also free. It has yet to be determined whether she was born free or obtained freedom either by manumission or self-purchase. No such records could be located at the Baldwin County Probate Court.

20) George’s next-door neighbor, in 1870 was Nathaniel Hall. Nathaniel was related to wealthy Charles Hall, deceased since 1843. In the 1830 U.S. Federal Census, Charles Hall had in his household a free woman of color with her minor daughter. This could have been Charlotte Ficklin. No record was found to support this in the Baldwin County Probate Court holdings. However, it is a likely nexus for George being acquainted with Nathaniel Hall. No evidence was found to support Nathaniel Hall being a slaveholder in either the 1850 or 1860 U.S. Federal Census Slave Schedules. Nathaniel Hall apparently was uniquely abolitionist in his practices. This was a remarkable finding.

21) Additionally, no record of any Ficklin(g)s in either Baldwin or Mobile County as slaveholders was found in the 1850 or 1860 Slave Schedules. This was also remarkable. So, whatever her legal status, Charlotte and her children lived free and unencumbered by slavery.

22) The boundaries of Mobile County and Baldwin County changed several times.

It may be concluded from the genealogical evidence presented above that:

a) George Ficklin, born 1834, in Mobile County, died 05 Oct 1889, in Baldwin County, was a free person of color in both locales.

b) George Ficklin purchased real estate prior to the inception of the Civil War, as a free person.

c) George Ficklin enlisted in the military as a free person, during the Civil War.

d) George Ficklin’s parents were free persons prior to Emancipation, therefore he enjoyed the privileges of freedom as a non-indentured citizen of Alabama.

e) George Ficklin’s society included other land-owning free persons of color from Mobile. (Fanny and Richard Foster were married in Mobile County, Alabama.)

And thus, given the foregoing conclusions, George Ficklin lived free in Creole Mobile, prior to the Civil War.

George Ficklin, 1834-1889

GEORGE FICKLIN

GEORGE FICKLIN